With the collaboration of Celia Guijarro

“Natural” is at present more than anything else an advertising appeal used by marketers with the purpose of engaging consumers both with products and values. This double consequence has proved to be tempting for them to design the marketing policies of a wide range of objects.

At the supermarket, if we take a closer look at the cartons of milk, oat, soy… or at the boxes of cereal, we will realize that they come with explicit messages that emphasize their supposedly natural qualities. Some of the expressions we would find are the following: “all natural and no artificial flavors”; “the most natural product”; “100% natural food”. These slogans are accompanied by references to other kinds of benefits: it is good for the planet, it is sustainable, it has no preservatives, it does not contain genetically modified organisms or any “secret” ingredient.

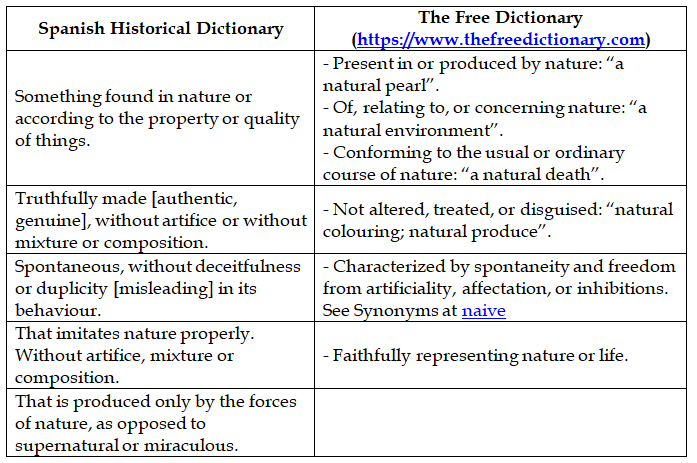

The idea that a product considered natural has an added positive virtue and consequently is good for the consumer, derives from associations embedded in cultural values. The mere consultation of a dictionary can help us understand the imaginary connections sparked in our minds when that adjective is used. If we look up the word “natural” in the New Spanish Historical Dictionary –from the Royal Spanish Academy–, which is available online (http://web.frl.es/ntllet/), we obtain some meanings that have been dominant in western cultures since at least 1782. In the table below we present the most relevant results for the purpose of this analysis, compared to the meanings available in The Free Dictionary, which is accompanied by the informative thesaurus of the term “natural” reproduced below:

The key word “natural” and its associations according to the thesaurus available at The Free Dictionary (https://www.freethesaurus.com/natural) are represented in the following graph:

The marketing strategy that transforms certain meanings or social values into remarkable features of a particular product that enhances its qualities can be traced back in the case of “natural products” at least to 1850, as the following examination of Spanish representative newspapers from that period on proves. In this approach we have searched references in the advertising sections within the period that runs from 1850 to 1940.

The first conclusion we came up with was that the term “natural product” from 1850 onwards was mainly a part of health, dietary supplements and cosmetics advertising campaigns. Next in number of references is its use in the group of foods. Finally, there was a third group, consisting of industrial items, that had very few mentions.

Here we present a selection of significant advertising campaigns and their illustrations concerning the groups mentioned.

Health, dietary supplements, cosmetics and food

Mineral water is a commercial invention and one of the most representative examples in the collection of traditional natural products. Brand advertisements usually contained long explanatory texts describing the multiple healing properties concerning the consuming of water that comes from a specific location. An ad from 1880, for example, said that the Agua mineral natural de Carabaña had “decisive application in many, but especially in certain and painful ailments. […] [For instance] in cases of jaundice, persistent constipation […] in heavy digestions […] in the digestive tract and […] herpes, lymphadenitis, rheumatism and syphilis, etc.” (El Imparcial, 19/12/1880)

“Natural products” are presented as substances that are safe and harmless:

- This is the case of Píldoras de cáscara Midy-Luidy, “soft and safe” (Revista de Especialidades Médicas, 1906).

- La magnesia Roly. Fosfosiliciada, “made up of harmless and natural products” (La Vanguardia, 25/12/1927).

- Gaba, a tablet consisting basically of liquorice extract which is presented as effective against colds, adding that “you can take as many you want without risk to your stomach”. (La Vanguardia 23/11/1930).

- La magnesia Roly (1927)

- Gaba (1930)

“Natural products” are not related to any artificial or chemical process:

- Sel Vichy Etat, “Natural product extracted from the springs of the Vichy state (France). Produces an excellent alkaline drink, superior to all artificial specifics” (La Época, 21/11/1922).

- Ovomaltine (from latin ovum, egg, and malt) Wander. The ingredients were malt, milk and egg flavoured with cocoa. It is recommended to regain health after any illness, especially flu, and it is announced as being superior to any drug-based product (La Vanguardia, 25/2/1931).

- La medicina vegetal del abate Hamon. “Plantas que curan [Plants that heal]”. It gives information about a book that contains herbal remedies. The text of the ad reminds consumers that “You must bear in mind that taking drugs with chemicals is unnatural”. So there is no harm in taking it (La Vanguardia, 14/5/1931).

- Hervea. The ad ensures that “If you suffer from rheumatism, this wonderful plant will produce you greater relief in one-month than chemicals or other very expensive treatments will in a year” (El Heraldo de Madrid, 18/1/1932).

- Vermouth Cinzano. The message for the consumer in this case says that the great advantage of this vermouth over other similar beverages is that it is not a “chemical composition”; it is only made up of natural products. (La Vanguardia, 21/5/1925).

- La medicina vegetal del Abate Hamon (1931)

- Hervea london (1932)

Additional persuasive information consists in emphasizing that “natural products” are rich in vitamins and provide energy and vitality:

- Sri sémola Carsi (rice semolina) (La Vanguardia, 19/5/1926).

- María Artiach y Chiquilín (biscuits) (La Vanguardia, 27/4/1932).

- Coca-Cola (La Vanguardia, 3/8/1928).

- Bishop’s Natural Fruit Saline (Ahora, 24/4/1934).

- Extracto de Carne Liebig (meat), (La Moda Elegante Ilustrada, 30/12/1912).

- Sri Semola Carsi (1926)

- María Artiach y Chiquilín (1932)

- Coca-Cola (1928)

- Extracto de carne Liebig (1912)

Some ads, especially those concerning mineral waters, make explicit the origin of the product, that sometimes comes from exotic lands or from places far away from urban civilizations:

- Agua mineral natural de Carabañas (El Imparcial, 19/12/1880).

- Sel Vichy Etat (La Época, 21/11/1922).

- Leche de Islandia Vasconcel-París (La Vanguardia, 30/10/1928).

Others use the argument from authority (also called an appeal to authority, or argumentum ad verecundiam), that normally contains a reference to science or a scientific practice:

- Sri sémola Carsi, “with scientific techniques to keep all its natural richness”.

- Quaker Oats, “The Men of Science especially recommend Quaker for its great nutritional qualities […]” (Mundo Gráfico, 22/2/1928).

- Quaker oats (1928)

Conclusion

Imaginary antagonisms work well in publicity (and in politics). The opposition natural-artificial was something installed in people’s imagination and reinforced by advertising. Later it was represented in visible and tangible objects, in products that could be acquired in groceries and supermarkets. But that opposition is tricky and extremely difficult to establish (see on this blog Natural versus artificial). If we consider “natural” as something that is absolutely in the same state as we find it in nature, without the intervention in any sense of the human being, then olive oil and animal farms are not natural. But obviously they are not artificial objects. The chemist José Manuel López Nicolás, author of the book Un científico en el supermercado. Un viaje por la ciencia de las pequeñas cosas [A scientist in the supermarket] (Planeta, 2019) says in his blog (https://scientiablog.com/2014/05/05/el-marketing-emocional-y-los-alimentos-naturales/):

“I’ve always defended that the term “natural” applied to food is a fad without any meaning. No, today I am not going to talk about chemophobia … but at this point no one has been able to tell me, with scientific criteria, what a natural product is, what it consists of, what advantages it has compared to an “unnatural” one … In fact, the European Food Safety Authority does not recognize any allegation of “natural products” so that food companies are not authorized to advertise any healthy property associated with a food for the simple fact that it is considered “natural”.

A first approach to define natural products was suggested when a contrast between organic chemistry (related to living organisms, plants and animals) and inorganic chemistry was accepted in the early 19th Century . But this separation was blurred when the German chemist Friedrich Wöhler succeeded in synthesizing urea, a natural product found in urine, and when twenty years later the German Professor Adolph Wilhelm Hermann Kolbe synthesized acetic acid from carbon. And at the end of the same century it was demonstrated that there was not something specific to nature –such as a vital force–, so the physical-chemical laws work basically in the same way either in living and non-living organisms. But these reformulations and changes were taking place in the academic circles. Popular and advertising assumptions, as we have seen, still relied on radical distinctions and on the appeal of “Mother Nature”. The reason for this should not be attributed to ignorance, but to ways of living, religious beliefs, the persistence of the Hippocratean “healing power of nature”, and other interests (sometimes spurious as it is properly revealed in the book written by J. M. Mulet, Los productos naturales ¡Vaya timo!, Laetoli, 2016).

References and further readings

INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIÓN RAFAEL LAPESA DE LA REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA (2013), Mapa de diccionarios [en línea]. http://web.frl.es/ntllet

LÓPEZ NICOLÁS, José Manuel (2019), Un científico en el supermercado. Un viaje por la ciencia de las pequeñas cosas, Barcelona, Planeta.

LÓPEZ NICOLÁS, José Manuel (2014), “El marketing emocional y los alimentos naturales”, en Scientia (blog), 5 mayo 2014, https://scientiablog.com/2014/05/05/el-marketing-emocional-y-los-alimentos-naturales/.

MULET, J. M. (2016), Los productos naturales ¡Vaya timo!, Pamplona, Laetoli.

THE FREE DICTIONARY, https://www.thefreedictionary.com/